By Tamara Layden

“Our stories belong in the community. They do not belong to the university or the government. They are ours–our data–and they belong to the Aboriginal community where the research is being carried out.”

Pamela Croft-Warcon (Yuwaalaraay) in Lori Lambert’s book, Research for Indigenous Survival

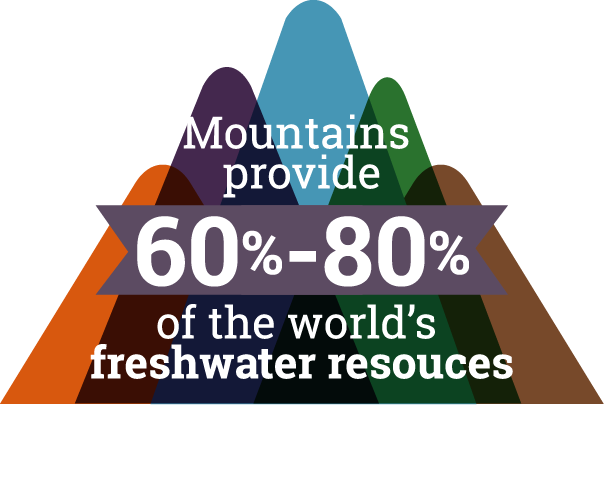

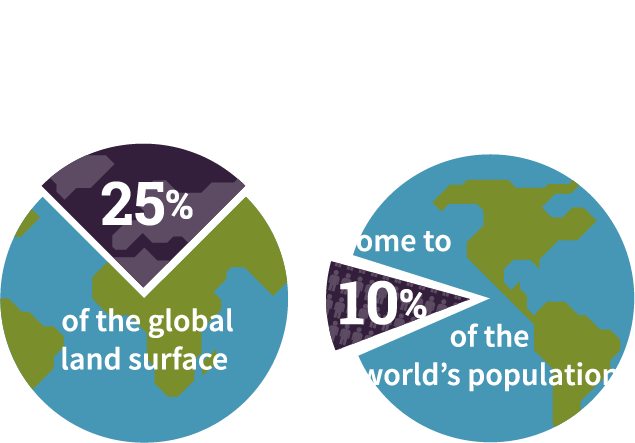

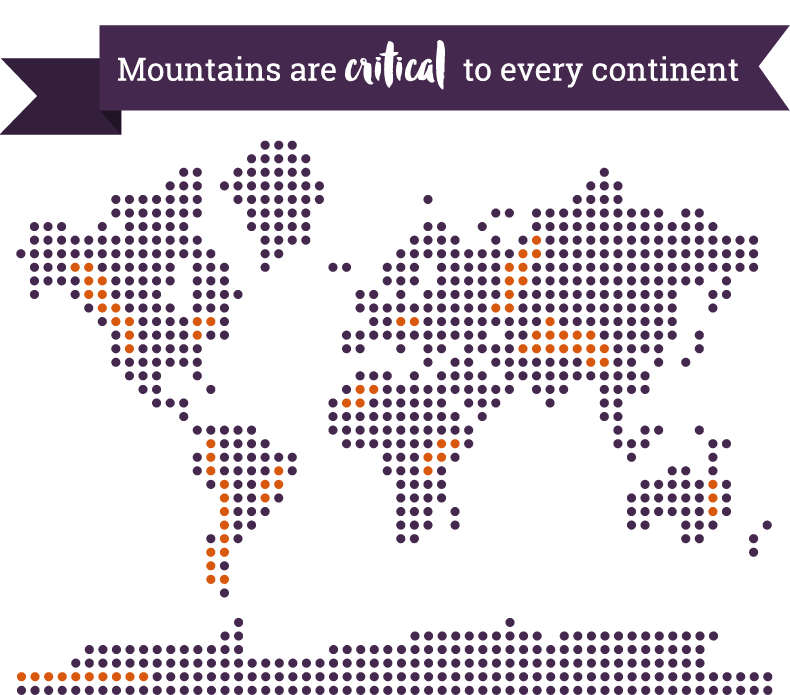

Convergence science research aims to bring together diverse worldviews and knowledge systems to address complex and interconnected social-ecological issues. In alignment with these broader convergence science efforts, Mountain Sentinels brings together a diverse network of local, regional, and international partners focused on strengthening environmental sustainability across the world’s mountains.

At the initial Mountain Sentinels Network convening in 2022, community attendees identified Ethical Space & Data Governance as being one of the core principles and priority “seeds” of the work of Mountain Sentinels. This seed specifically aims to support balanced relationships that account for the legacies and ongoing realities of colonial harm against Indigenous Peoples globally, to build meaningful, culturally-relevant sustainability solutions across all our efforts.

At the initial Mountain Sentinels Network convening in 2022, community attendees identified Ethical Space & Data Governance as being one of the core principles and priority “seeds” of the work of Mountain Sentinels. This seed specifically aims to support balanced relationships that account for the legacies and ongoing realities of colonial harm against Indigenous Peoples globally, to build meaningful, culturally-relevant sustainability solutions across all our efforts.

The remainder of this blog outlines key resources and offerings that stem from this Ethical Space & Data Governance seed for our networks of scholars, researchers, and community members to continually attune our practices towards supporting community needs, interests, and futures.

Co-Creating Ethical Space for Convergence Science Research

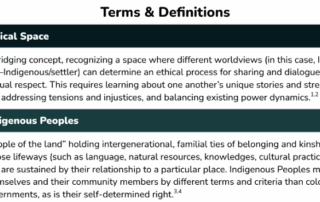

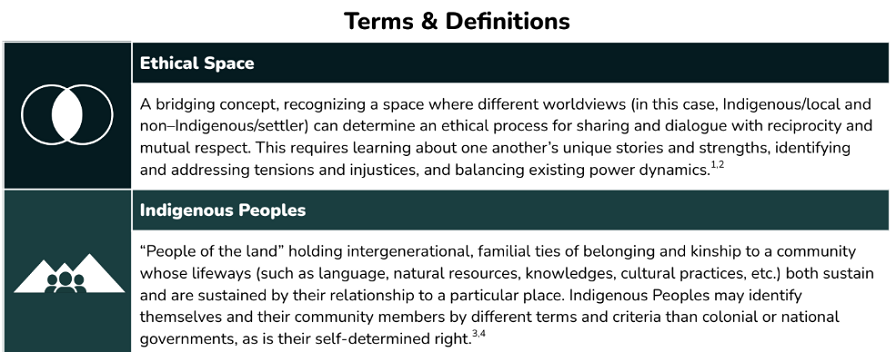

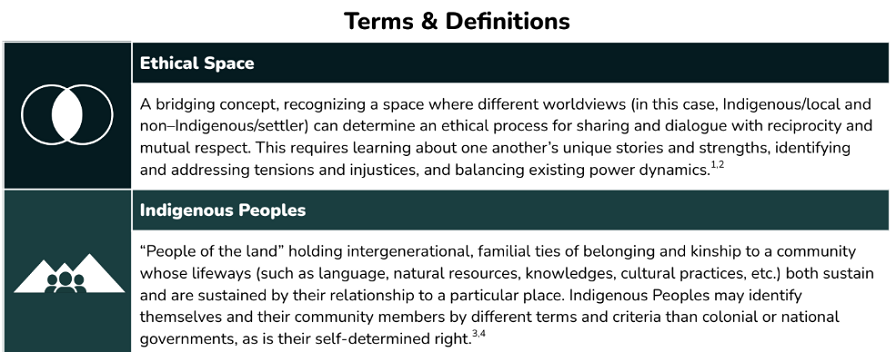

In building balanced relationships in convergence science, the concept of Ethical Space, as described by Cree Elder Willie Ermine, offers protocol for engaging respectfully across worldviews. Specifically, Ethical Space is a bridging concept that recognizes the space where different worldviews (in this case, Indigenous/local and non–Indigenous/settler) can determine an ethical process for sharing and dialogue with reciprocity and mutual respect. Co-creating this dynamic space of mutual consideration and understanding can take on many forms and is strengthened by shared values and responsibilities that support Indigenous leadership, goals, and interests to rebalance the scale. The relational science model is one example framework (out of many) that offers specific process-based guidance and examples for working within an Ethical Space in support of Indigenous rights and relationships (see this resource as well for another example of the relational science model applied to conservation in Latin American contexts, also available in Spanish).

Strengthening Indigenous Data Governance in Convergence Science Research

As we are thinking about long-term sustainability of ecosystems, we must also consider the lifespan of project information (data) and corresponding data stewards. With the rise of large, open-source datasets, it is necessary to ensure that the Indigenous Peoples can reliably access and control their own data and embody Indigenous cultural protocols for knowledge stewardship (see CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance–Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility, and Ethics) to ensure Indigenous data sovereignty or the the fundamental right of Indigenous Peoples to govern the collection, ownership, and application of their own data. Indigenous data governance, on the other hand, are the tools applied to support Indigenous data sovereignty as aligned with community interests and cultural protocols.

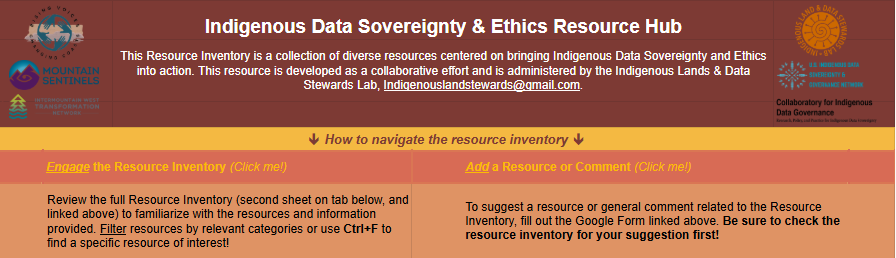

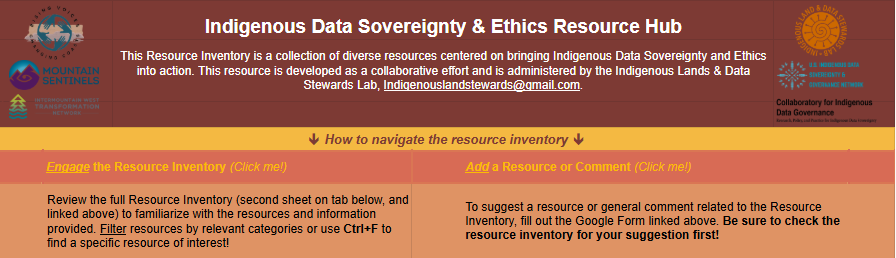

Today the Indigenous Data Sovereignty & Governance movement spans countries, disciplines, and diverse and extensive community contexts. As momentum builds, below we share two offerings to support your Indigenous Data Sovereignty & Governance efforts, beginning with 1) a Resource Bundle that shares key terms, definitions, and guiding frameworks, and 2) a Resource Inventory for self-guided learning. Both of these resources aim to help organize information that could be relevant to your projects and collaborations wherever they may be strengthening Indigenous data futures. These resource offerings were created as part of a larger harmonizing effort between Mountain Sentinels, Indigenous Lands & Data Stewards Lab, the Collaboratory for Indigenous Data Governance, US Indigenous Data Sovereignty Network, Rising Voices, Changing Coasts, and the Transformation Network.

1. Resource Bundle

The Indigenous Data Sovereignty & Governance Resource Bundle offers terms and resources that provide an entryway into understanding Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Governance, including definitions of key concepts and foundations of the movement. Specifically, this Resource Bundle focuses on rights-based frameworks such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance, and Local Contexts, which offers tools to reassert cultural authority in Indigenous data. We recommend starting with these frameworks if Indigenous Data Governance in particular is new to you.

2. Resource Inventory

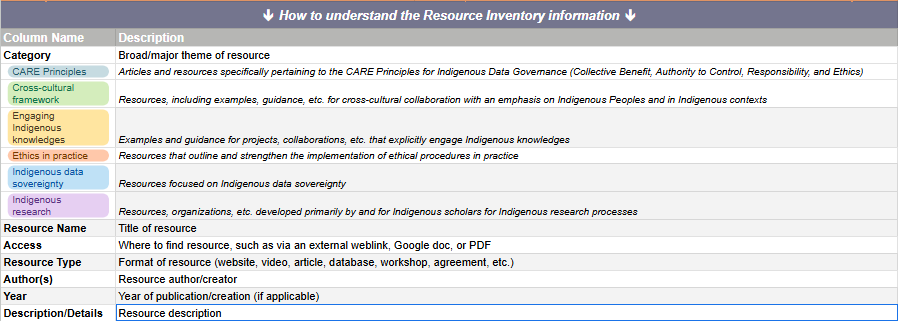

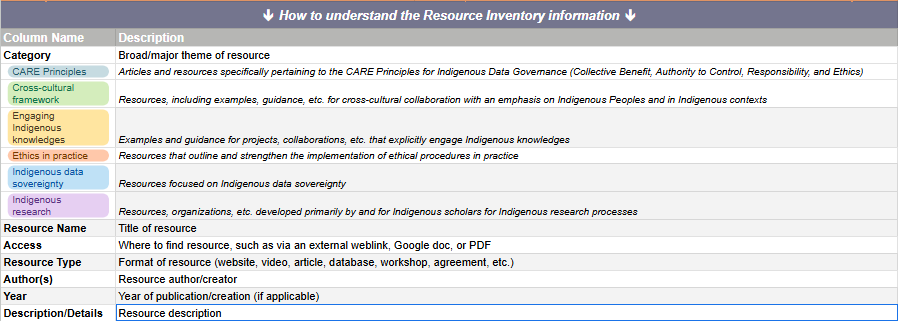

Expanding from the Resource Bundle, the Data Sovereignty & Ethics Resource Inventory compiles resources related to guidance and practical applications of Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Governance. On the initial introduction page of the Resource Inventory (first sheet), you will find a road map of content, including a direct link to the resource inventory list and a link to a Google form to share your own resources and contexts to contribute to these broader efforts.

Scrolling down the page, you will find more details on how the resources are organized, including the categories and topics included in the resource inventory.

The second sheet of the Resource Inventory offers a list of resources, complete with resource categories, names, access links, and descriptions. We know that resource lists can be overwhelming, so we recommend filtering by different categories or searching for relevant resources or key words (using Ctrl+F on your keyboard) based on your learning focus.

We hope that these resources can offer an entryway into building a deeper understanding of these topics. We also want to emphasize that there is no one perfect resource or one right way to learn as this work is meant to be dynamic and responsive to your own contexts. We appreciate engaging with you in these collective efforts and look forward to connecting more together as the work continues.

Suggested citation: Layden, T. J. 2025. Co-creating ethical space for convergence science research & Indigenous data governance. Mountain Sentinels.

Tamara Layden is a program coordinator, data scientist, graphic artist and collaborator with the Indigenous Lands & Data Stewards Lab who recently earned a doctorate at Colorado State University. Learn more about Tamara’s current projects here.