By Julia A. Klein

Inside COP30: A Mix of Progress and Deep Disappointment

At the heart of the Amazon, the world gathered to decide the future of the climate, and fell short. Even in the chaos of 60,000 people and nearly 200 nations, one thing was clear: the world is hungry for climate action, but the biggest roadblocks persist.

I was fortunate enough to spend November 11–28 on the ground at COP30, the 30th Annual United Nations Climate Change conference in Belém, Brazil. I was there wearing many hats, including as a CSU professor, co-director of the Mountain Sentinels Alliance, and head of the Instituto de Montaña delegation, a Peru-based NGO and the head of the Mountain Sentinels Latin America Collaboratory. I was also part of a documentary film team following Saúl Luciano Lliuya, whose lawsuit against energy giant RWE helped reshape global climate litigation.

A Blue Zone Buzzing With Ambition

COP30’s Blue Zone is the epicenter of official UN negotiations, and it felt like a climate world fair. Nearly 200 nations participated in the formal negotiations, and governments, NGOs, and coalition groups hosted two-week-long pavilions, daily events, side events, press conferences, and exhibits. Beyond the Blue Zone, there were other venues and activities, including the People’s Climate Summit, the Climate March, and the Green Zone, but inside the Blue Zone was where I was focused.

For me, the atmosphere at COP is one of high energy, creativity, and hope. Visually, it is a tapestry of cultural symbols and narratives. The Indian pavilion is always earthy and aesthetically beautiful. The Portugal pavilion gave out free wine in the late afternoon and supported conversation and camaraderie. Life-size pictures of the charismatic animals of the rainforest decorated the temporary walls of the vast blue zone. Country pavilions showcased their climate ambitions and successes to date (and yes…the greenwashing). I was surprised to see the Climate Mobility Hub, front and center, quietly acknowledging the loss and damage we are already facing. A giant plastic Earth hangs from the ceiling above the exhibits as a silent reminder of what’s at stake.

Energy, creativity, culture, and negotiations hum in every hallway. Standing there, it feels like being at the center of the entire planet, trying to figure out its future.

Where Was the US?

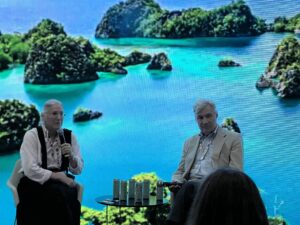

Sue Biniaz, the Principal Deputy Special Envoy for Climate Under Secretary of State John Kerry, interviews Senator Whitehouse (RI) in front of a US audience, mostly US students and other university participants and activists.

The Trump administration did not send an official US negotiation delegation to COP30. Former US negotiators who were there in an unofficial capacity shared with our students that the absence made it harder to get deals across the finish line. Historically, the US has worked behind the scenes to broker agreements, but this year its presence was missing from the negotiation rooms.

But the US wasn’t entirely absent. Governors, mayors, and local leaders from 26 states participated in the Local Leaders Forum, held in Rio de Janeiro just prior to COP30. At COP itself, California’s Governor Newsom made waves during the first week, signing methane agreements with Colombia and EV expansion agreements with Nigeria. America’s All In and the US Climate Alliance – which represents a large percentage of the US economy and emissions – were also represented at COP.

Senator Whitehouse from Rhode Island was the only member of Congress in Belém. He met with our students and others from the US and shared the following:

“As long as the fossil fuel industry enjoys the freedom to pollute for free, we will never find that pathway to climate safety.”

“It is not the natural state of America that we are partisan, divided on climate. It is an artificial state created by billions and billions of dollars in fossil fuel spending…”

Civil Society Rises

One of the bright spots of COP30 was the Research and Independent Non-Governmental Organizations (RINGO) community, made up of researchers, universities, and independent NGOs. It’s also one of the nine constituencies recognized by the UNFCCC. CSU and Instituto de Montaña/Mountain Sentinels teamed up with partner universities for a week-long exhibit showcasing climate work from Colorado to the Andes. Instituto de Montaña/Mountain Sentinels also held an official side event in week 2 at COP titled “Amplifying Global South Voices for Climate Action and Policymaking”, along with the US National Academy of Sciences, the University of Arizona, and Emory University.

Students were on the frontlines of COP, meeting negotiators, asking hard questions, and seeing firsthand how decisions made in closed rooms ripple through mountain communities worldwide. The amount of cross-cultural knowledge sharing, alliance building, and camaraderie that develops from shared purpose is an inspiration, and our students return truly changed from this experience.

“Amplifying Global South Voices for Climate Action and Evidence-Based Policymaking”, our side event at COP30.

Indigenous Leadership: More Visible Than Ever, Still Fighting for Power

Hosting COP30 in Belém, known as the “gateway to the Amazon,” was intended to elevate the voices of Indigenous peoples, another UNFCCC constituency group. While the numbers increased to 900 Indigenous delegates, up from 300 last year in the Blue Zone, many felt representation was symbolic and not particularly substantive.

But presence is not power. Even with that growth, there were more than twice as many fossil fuel lobbyists inside the Blue Zone. And Brazil moved forward with new exploratory oil drilling just before COP began.

COP30 President, Ambassador André Corrêa do Lago, a veteran Brazilian climate diplomat from Brazil’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, with Brazil’s Minister of Indigenous Peoples, Sônia Guajajara, as the COP Presidency meets with the Indigenous People’s Constituency.

Indigenous peoples led powerful demonstrations, shared climate solutions rooted in generations of land stewardship, and demanded recognition of their lands and real inclusion in national climate targets. Early in the week, protesters broke through security to enter the summit; other peaceful demonstrations blocked access to the venue. Saúl Luciano Lliuya participated in a Greenpeace action and interactive climate damage exhibit, urging governments at COP30 to roadmap to phase out fossil fuels and make polluters pay.

Our Mountain Sentinels/Instituto de Montaña delegation aimed to bring four Indigenous Fellows to COP. Shantal Pacotaype Mendieta contributed to the exhibit and was interviewed by ClimaTalk. Ana Gabriela Pumacayo Marcabellaca contributed to the exhibit, spoke at the Voices from the South side event, and translated for Saúl in different capacities. However, even with funding and accreditation, barriers like visas, travel, and language limited participation. One of our Fellows from Cameroon could not obtain a transit visa; another, who spoke Quechua and Spanish, found many events inaccessible due to English-only programming. This is what inequity in climate spaces looks like.

The Outcomes: Steps Forward and Back

Overall, COP30 was meant to set clear pathways and to deliver commitments to put the world on a safer climate trajectory (e.g. limit warming to 1.5°C by 2035, which would require a 55% reduction in current greenhouse gas emissions to achieve). The hope was that countries would commit to pathways to end fossil fuel use and halt deforestation.

Despite more than 80 countries willing to commit to moving away from fossil fuels, the final negotiated document did not mention the word “fossil fuels” at all, due to pressure largely from the petrostates. As someone who has studied climate impacts in mountain regions for 30 years and taught CSU’s first climate course 20 years ago, that omission is quite depressing.

But there were meaningful wins:

- 119 countries submitted new national commitments to address climate change.

- A global target to triple adaptation finance for climate adaptation.

- A new tropical forest conservation fund in Brazil.

- The Brazilian government announced progress in demarcating 20 Indigenous Lands, representing millions of hectares.

- The Brazilian Presidency intends to move forward with roadmaps to phase out fossil fuels and deforestation outside of the formal COP talks.

- Cities, states, and private sectors pledged to push forward ambitious climate plans

It’s not enough, but it is forward motion.

One U.S. negotiator left our students with advice that landed with all of us: “We need everyone, everywhere, all at once.”

For mountain communities and environments, and for every place we love that’s already changing, COP30 was a reminder that this work can’t wait.

This blog was written by Julia Klein, in collaboration with Protect Our Winters. Klein is part of the POW Science Alliance. She will write a future blog that focuses on COP30 and mountains.