Tual Sawn Khai

Country Coordinator of Myanmar -16th UN Climate Change Conference of Youth

PhD Candidate in Sociology and Social Policy

Lingnan University, Hong Kong

How has COVID-19 impacted my community?

My community, Tuisau Village, is located in the highlands around 30 miles from Kalay City, Sagging Region, and 20 miles from Tedim Township, Chin State, in Myanmar. The first Myanmar COVID-19 patient, 001, was confirmed on March 23rd, 2020 in Tedim Township, Chin State.

Chin State is the most improvised state in Myanmar, and 58% of the population lived below poverty in 2017 (World Bank, UNDP, and Central Statistical Organization, 2018). For a century, Chin people, including my community members, have relied on shifting cultivation, which involves cutting and burning forest to make way for farms. They have no electricity and rely on collecting firewood for cooking and lighting. In 2015, when mudslides and landslides destroyed over 6069 acres of farmland, 28 religious buildings, 55 school buildings, and 303 bridges in Chin State (UNICE, 2015), my community village was no exemption.

My entire community village relocated approximately one mile from its previous location. In addition, my community members were promoted to migrate internally and internationally to earn a living due to the rising food insecurity caused by low soil fertility and climate change. Before the pandemic, they relied heavily on migrant remittances for living; however, following the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak in 2019 from Wuhan, China, my community members who work in foreign countries also suffered employment losses in their respective destinations. They have been unable to send remittances, and their family members left at home have struggled to survive to buy food and basic needs.

Aside from the rising food insecurity, Chin State has the most inadequate healthcare facilities and remains in the highest maternal mortality rate of 356.7 (per 100,000 live births), the highest child mortality rate of 75 (per 1,000 live births), and 0.99 health workers per thousand people (Chin State Health Report, 2018). When the first confirmed case was discovered in Tedime Township, the Tedim General Hospital did not have an Intensive Care Unit (ICU), just two doctors and a few nurses, and no other sufficient personal protective equipment. In that regard, Tedim Hospital demanded that the patient be transferred to Falam General Hospital, where ICU is available. Unfortunately, the local people of Falam rejected that request. Further, the people from Tedim Township, including my community members, have also been labelled as virus spreaders and faced discrimination even when buying their daily basic needs.

Additionally, the COVID-19 test kit was only available in Naypyidaw, Mandalay, and Yangon city for the first one to three months of the outbreak in Myanmar. The suspicious patient swabs were mainly sent to Yangon, and the test results took a week to be known due to travel restrictions. People diagnosed with other illnesses, such as food poisoning, had to go through a COVID-19 health check. The doctor only gives medication to patients after the results of the tests are known. One of my community members died as a result of the lack of urgent medication treatment.

Following the military coup in Myanmar on 1 February 2021, health workers initiated the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) on 3 February, which was quickly joined by public teachers and civil servants from various sectors to express their dissatisfaction with the military coup. Chin State has 70% or the highest percentage of CDM in Myanmar (Khonumthung News, 2021). Consequently, the public hospital has been closed, and the number of COVID-19 cases remains unknown in Myanmar, including in my community.

The World Food Program estimates that nearly 3 million people in Myanmar are already hungry and that 3.4 million will go hungry in the next 3 to 6 months as a result of the COVID-19 disruption and the political crisis that takes place since 1 February 2021 (Robinson, 2021). My community is not exempt from such disaster or food scarcity. For the time being, my community needs different forms of assistance to continue surviving and an alternative/informal education program for school children due to the uncertainty of school reopening during the pandemic. The primary and middle school in my community has been closed since March 2020 until today 2021. Unlike children in the city, children in my community do not have access to online learning or other informal learning.

How has my project benefited my community?

I was able to distribute one box of surgical masks, 12 kg rice, four bathing soap (Dove), one litter of oil, 1 kg of beans, and 2 kg of cooking salt to each of the 73 households to help the immediate basic needs of my community and to protect their health. I am grateful to Mountain Sentinels for the funding support and to my parents for their assistance in purchasing the materials in Kalay, City.

It took approximately a day by small light truck from in Kalay, Sagaing Region, to reach my community “Tuisau” Village, Tedim Township, due to poor transpiration road.

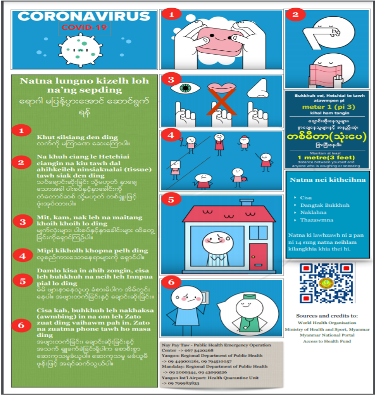

Distribution and dissemination of COVID-19 Pamphlet

To protect my community’s health and well-being, I distributed a COVID-19 awareness information pamphlet in the local language, a hand sanitizer, and one box of masks to each family member to raise their awareness of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Before disseminating and distributing the COVID-19 information pamphlet in the local language, my community members were unaware of why they have to maintain social distance and wash their hands often to protect themselves from COVID-19. There was no information dissemination in the local language they understood. They have no access to the internet and television service. They did not receive any personal protection equipment, such as masks or sanitation facilities, from NGOs and the government.

Only those who completed the dissemination of the COVID-19 awareness information session in the local language were distributed the materials. My community members were so grateful to Mountain Sentinels for the generous support. They admitted that they do not need to worry about food for at least a week since they receive rice, oil, and bean as they have been worrying about it all day and night since the pandemic outbreak.

In addition, they still need continued support to overcome the pandemic and the food shortage. In the long run, they need further assistant in creating a sustainable livelihood program to boost their income generation, as migrant remittances cannot depend on making a living for the long term. Also, implementing comprehensive environmental education and replanting trees in my community areas are needed to fight climate change.

Reference:

Khonumthung News. (2021, 12 March). Most Govt Staff Join Civil Disobedience Movement in Chin State. Burma News International. https://www.bnionline.net/en/news/most-govt-staff-join-civil-disobedience-movement-chin-state#:~:text=Over%20seventy%2Dpercent%20of%20government,Civil%20Disobedience%20Movement%20(CDM)

Robinson, G. (2021, 22 April). UN warns of Myanmar’s worsening food shortage as turmoil deepens. Nikkei Asia. https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Myanmar-Coup/UN-warns-of-Myanmar-s-worsening-food-shortage-as-turmoil-deepens#:~:text=BANGKOK%20%2D%2D%20Up%20to%203.4,Food%20Programme%20warned%20on%20Wednesday.

UNICEF. (2015). Chin State July / August 2015 Landslide Situation Report 19th November 2015. (). Hakha, Chin State, Myanmar: UNICEF.

Central Statistical Organization (CSO), UNDP and World Bank. (2018). Myanmar Living Conditions Survey 2017: Key Indicators Report.