As winter solstice is upon us and darkness hovers in the far north and south, Chris Cosgrove, PhD student at Oregon State University and Early Career Mountain Sentinels member, shares his zany fieldwork experiences from the Wrangell Mountains in Alaska from earlier in the year.

Up Wait Creek Without a Pilot

“… Doable but a little boggy” was the expert local knowledge. What we were missing was any knowledge about expert local knowledge. Translation: “Possible, but you’ll be spending two days pulling your boots out from cold, knee-deep, sucking mire, alternated with tripping over ankle-rolling tussocky tundra.”

Seventeen miles, I think by most people’s estimations, is a good day’s hiking for a group of vigorous young scientists. Especially if a glance at the map reveals the 17 miles to be a designated trail gently decreasing in elevation to its end. An end conveniently near a Sportsman’s bar known to be well-stocked in assorted refreshments, and this being Alaska, frozen pizza. Even after five days tramping in the mountains, installing remote cameras to capture snow conditions, taking a couple of days to cover the ground should be a literal walk-in-the-park – or in this case, the Wrangell St. Elias National Park.

Super Cub taking off from the local bar cum hunting lodges airstrip – on its way to Wait Creek in September. C Cosgrove.

The installation of remote cameras is to provide data on snow depth and habitat selection in support of a NASA project concerning the iconic Dall sheep, a wild species of thinhorn sheep found only in mountainous Alaska and northwestern Canada. Highly prized by trophy and subsistence hunters alike, due to being burly, and supposedly tasty, beasts that live in high, tough terrain, as with many trophy species their magic also attracts the common nature-loving tourist. As such, there are significant economic possibilities for local residents in areas otherwise characterized by their wildness and remoteness. The above-mentioned Sportsman’s bar is evident of this, being adorned inside with busts of big wildlife and, alongside an airstrip, has numerous cabins to rent. You don’t need to see the camouflaged attire of its customers to know who they’re catering for. With guided hunts for Dall Sheep beginning at USD20,000 and steeply increasing, back-country businesses are built around the six weeks in August and September that are sheep hunting season. For our project, this time offers an important impetus for research, but also, as it turns out, a revealing obstacle to fieldwork, culminating in hiking two days across “fundra”.

Total Dall sheep populations have decreased 21% since the 1990s, following as high as 60% population declines in some areas during the 1980s. A leading cause hypothesized for these population declines is increasing hazardous weather events during winter, and particularly in April and May, during the Dall sheeps’ critical lambing period. Warmer temperatures could be causing melting of the snowpack, or indeed instances of rain on snow, both of which refreeze into ice-layers that inhibit the sheep’s ability to access their forage. Other pressures stemming from a changing climate include ‘shrubification’ and potentially denser, thicker seasonal snowpacks from

Dall sheep rams on the move. A Pinzner

increased precipitation. Relying on access to open alpine meadows close to steep slopes to flee to from predators, if these meadows begin to close due to encroachment of shrubby plants such as willow, safe habitat and connection between herds is reduced. Indeed, the reduction of Dall sheep numbers may even be a contributing feedback to this phenomenon as they are a large ungulate whose presence and grazing maintains alpine ecosystem structure. Likewise, thicker, denser snow means greater energetic cost in digging for each chew of frozen fodder.

To begin to understand these processes atdifferent scales, our project combines a number of methodologies. The time-lapse cameras we’ve installed capture the rise and fall of snow depth in different locations at hourly intervals throughout the year, as well as the odd sheep. Detailed snow-surveys taken in March when the snow is roughly at its maximum complement this dataset. Both can then help constrain a spatially distributed and physically based snow evolution model, possible to run with climate reanalysis meteorological data from 1980 onwards. Such modelled data can be included in analysis with remotely-sensed data of vegetation change, GPS collar data monitoring of individual animal’s movement and survival, and historical aerial surveys of sheep populations and harvest records.

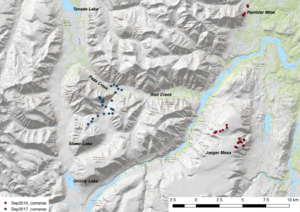

Map showing September 2016 (red) and 2017 (blue) camera locations.

Overall, fieldwork in year one of the project went serenely well. In September 2016, we flew cheerfully up in a two-seater “Supercub” from a local airstrip to Jaeger Mesa, a location recommended by an air service/hunting lodge as being well-populated by Dall Sheep. Conveniently staying in the air services’ cabin there, locating our cameras went smoothly, even though we were defeated in getting a transect down to tree-line, given the sheer height of the place.

Fieldwork in year two has proven a little more challenging. Early in 2017, we began to realize that no sane pilot in Alaska would be willing to land on the Mesa with a ski-plane! Inaccessible by any other sensible method, we had the great fortune of securing extra funding to instead fly up in a helicopter to do the March snow surveys in cold, but blessedly-calm weather. As helicopters are expensive and extra funding was a once-off opportunity, a new site, accessible by snowmachine, was needed for winter 2017/18. Finding the site proved easy. Wait Creek, 10km west of Jaeger Mesa, had its own rough airstrip and the promise of established snow-machine trails from trappers during the winter. Wishing to leave our cameras up on the Mesa for the longest time possible before moving them, the week before hunting season opened in August was set for taking them down. Not wishing to leave desirable and expensive equipment up in the mountains for anyone to borrow, the middle of September was hence decided as the best time to redeploy – hopefully before the snow comes in and after everyone’s bagged their sheep. Our friendly air service booked in our flights in June and all was set to go.

Except, just two days before it suddenly wasn’t. I naïvely asked whether we could negotiate the costs of the flights. Without much explanation they had gone up significantly since last September for the same trip. Turns out that air services don’t take kindly to even the politest attempts at bargaining around their busiest time of year. Flights cancelled. Cue panic…

Two nail-biting days later, as we flew up to the Mesa in beautiful August sunshine, a new pilot kindly described where I had gone wrong. Small air services calculate their fees not just on the pilot’s time per hour and the cost of fuel, but also the style of flying. Landing small planes on remote airstrips can be a dicey business; the chances of stones bouncing up and breaking expensive propellers apparently is fairly high for example. With all our equipment collected, finding a bush plane and pilot in the six weeks before our September (compared to the previous two day notice) redeploy seemed like it should be a breeze. But phone call after phone call was met with the same reply:

“Sorry can’t do it… moose hunting season, all booked up”.

The weeks went past and more elaborate plans were suggested.

“A colleague of a friend of a friend once had a plane in Anchorage and likes science.”

Colleague of a friend of a friend’s reply: “Moose-hunting”.

“Why not go on ATVs (All-terrain vehicle)?”.

Park Service: “…you’ll need a special permit and you won’t get it in time”.

“Pack horses?”.

As is often the case, asking the same question, just a little differently (and desperately) yields the solution. The air-service who saved us in August had one free day in the middle of looking after their moose-hunters. Getting us out though would be entirely dependent on weather and when the moose-hunters had got their kill. We could be waiting for weeks.

“So how difficult do you think it’d be to hike out?”

Relieved, I was easily persuaded by the answer to this question, and with silent prayer to the weather, persuaded three well-qualified field assistants that the hiking back part would be like the holiday after the work. For the fourth trip running, the weather was most obliging and the work was successful. After flying in and setting up camp, we were embraced by bright, dry days, perfect for what we were doing. As for the hiking holiday that followed, all can report a deep and physical understanding of the Alaskan understatement.

The August view from the top of Jaeger Mesa towards Mount Jarvis. A Pinzner

We’ll return to our cameras twice more; in March 2018 to conduct snow surveys and download data, then finally in June 2018 to take them down. Findings from our project will be taken forward into the second phase of NASA’s Arctic Boreal Vulnerability Experiment (ABoVE). In this second phase, focus moves from objectives concerning understanding of Arctic/Boreal Ecosystem Dynamics to objectives considering Ecosystem Services in the region.

More details on this research can be found at:

Project blog: https://dallsheep.weebly.com

NASA’s Arctic Boreal Vulnerability Experiment (ABoVE) : https://above.nasa.gov/